From November 30 to December 13, 2023, the United Arab Emirates (UAE) hosted the 28th United Nations Climate Change Conference known as COP28. Each year, COP convenes member states to determine global environmental ambition and responsibilities and to identify and assess climate measures. Ahead of this year’s climate summit, the UAE drew the ire of human rights and climate justice advocates who argued that a repressive petrostate with ongoing human rights violations should not be given such a prestigious position on the world stage.

From November 30 to December 13, 2023, the United Arab Emirates (UAE) hosted the 28th United Nations Climate Change Conference known as COP28. Each year, COP convenes member states to determine global environmental ambition and responsibilities and to identify and assess climate measures. Ahead of this year’s climate summit, the UAE drew the ire of human rights and climate justice advocates who argued that a repressive petrostate with ongoing human rights violations should not be given such a prestigious position on the world stage.

Historically, COP has presented a unique and timely opportunity to leverage the mobilization of global climate advocates to build cross-movement solidarity with victims of human rights abuse. It is also an opportunity to leverage media attention and state engagement to amplify key civic space demands. Yet, despite intensified global scrutiny of the country’s human rights record, UAE authorities continued their relentless campaign against human rights defenders and government dissidents. This has been viewed by the human rights community as a missed opportunity to protect civic space and to stand against the greenwashing of the UAE’s abysmal human rights record.

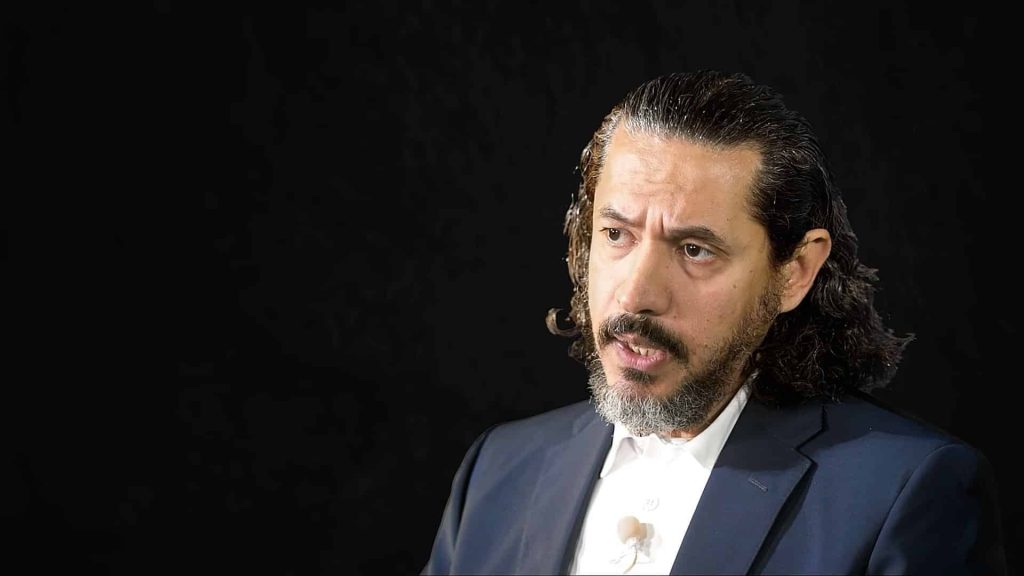

In this Expert Q&A, Emirati human rights activist and executive director of the Emirates Detainees Advocacy Center (EDAC) Hamad Al-Shamsi speaks with the Middle East Democracy Center’s Abdelrahman Ayyash and Yasmin Omar about the dire human rights situation in the UAE, efforts to build global solidarity with human rights defenders in the rich Gulf country, and the victims of the government’s transnational repression.

MEDC: International attention on the UAE’s human rights record during COP28 has not deterred the country from targeting human rights defenders. Indeed, during the climate summit, Emirati authorities began a new trial of 84 citizens on politically motivated terrorism charges, known as the UAE84 case. Can you describe the context of these trials and explain how the government uses the penal code and judicial system to restrict and suppress the human rights movement?

Hamad Al-Shamsi: We cannot start talking about the UAE84 case without first talking about its prequel, the UAE94 case. In 2012, Emirati authorities began arbitrarily arresting individuals—many of whom were peaceful democracy advocates associated with the Emirati group Al-Islah (Reform)—on trumped up charges, and continued until March 2013 when the mass trial officially began. The court sessions lasted for four months, after which 69 people received sentences ranging from 7 to 15 years of imprisonment. The authorities reserved the maximum penalty for those tried in absentia, while many of those within the country, such as Sultan bin Kayed Al-Qassimi, chairman of Al-Islah and a member of the Ras Al Khaimah Emirate’s ruling family, received sentences of 10 years in prison.

Though all of the detainees completed their prison sentences as of 2023, the Emirati government refused to release them and instead placed them in “counseling centers,” a method increasingly used to extend detention indefinitely. Apparently in an effort to improve their international image, UAE authorities attempted to legitimize these unjust detentions by bringing a new case, UAE84, against the detainees. The charges in this new case, however, were similar to those in the UAE94 case with only minor modifications, such as using the term “terrorist organization” instead of “secret organization.”

The UAE84 case, which began on December 7, 2023, appears to be a defiant message from authorities to the global human rights community, which had banded together to demand the release of Emirati detainees. The authorities brought this case while these organizations and world representatives were in the country to attend COP28. It is also a message to people in the UAE and to detainees and their families that they should not count on international support for their cases as the state would ultimately do whatever it wanted without regard to international law or even Emirati laws.

In addition, for case UAE84, authorities added at least two new people to the list of defendants: Nasser bin Ghaith and Ahmed Mansoor. Neither of the men had anything to do with the UAE94 case. Instead, they were detained in connection with their human rights work. They are now serving ten years in prison, which they were sentenced to in 2017 and 2018 , respectively. I believe that the authorities included them in the new case to make sure they remain detained after serving their current sentences and to prevent any potential international pressure to demand their release after their sentences are complete.

Does the UAE engage in transnational repression to target activists who are outside the country?

We can confidently say that after the arrest of Ahmed Mansoor, there are no activists in the UAE left outside prison. By arresting him, the authorities completely quashed human rights activism in the UAE. After that, the government directed its efforts to activists abroad. This included adding four people to the terrorist list in 2021, such as myself.

The UAE also restricts the movement of defendants’ families, barring them from traveling outside the country. On a personal level, the authorities have prevented my mother, my brothers, and my wife’s family from traveling, and continue to treat them as hostages to force me and others to return.

In another case, authorities revoked the citizenship of detainee Abdul Salam Darwish’s family while they were in the United States, and cut off state funding for the medical treatment of three of his children. One of his sons died when his medical treatment in the United States stopped. Even after the death of his son, authorities would not allow Darwish to contact his wife outside the country to console her.

One exile, Ahmed Al-Nuaimi, who resides with family in the United Kingdom, was subjected to a similar violation. Authorities did not allow his son, who is completely paralyzed, to leave the UAE and join his father. He died in the country and his parents were deprived from seeing him for the last time.

This harassment continues, as well as defamation on social media and intimidation of our social circles and acquaintances, to the point where friends refrain from meeting activists abroad. Some are even afraid to walk on the same street as us for fear that a picture might be taken that may be used against them later by the authorities.

Moreover, the Emirati government is able to exert pressure not only on human rights defenders, but also on the governments of the countries in which these defenders and activists reside. For example, as the UAE government strengthens its relationship with some countries and plans to make huge investments in them, the UAE requires the governments of these countries to silence UAE critics within their borders. This was the case with Qatar in relation to activist Alaa Al-Siddiq, who was unable to stay in Doha for a long time due to UAE pressure. Or with Jordan in relation to Khalaf Al-Rumaithi, who was deported to the UAE before his name was added to the UAE84 case.

This approach has become an integral part of the UAE’s tools of repression. When the government cannot deal with opponents directly, it links its international investments and partnerships to the partners’ ability to control critics of the UAE.

The UAE has also tried to use this method in other countries, such as the United States and the United Kingdom, by disrupting oil and gas deals, but it has not been able to achieve the same goal.

You were working with the human rights community in the Gulf for nearly a year to mobilize international solidarity with victims of human rights violations in the UAE. What challenges did you face and did you find the solidarity you were hoping for?

Ahead of COP28, we were seeking to achieve two goals. The first was human rights solidarity from international human rights organizations. We received great support from them, and we thank all the international civil society organizations (CSOs) that supported us. They showed support by signing onto joint statements, helping us spread awareness of human rights abuses in the UAE, and urging world governments to support issues of freedom of opinion, expression, and assembly in the country.

The second goal was related to international institutions and actors at the state level, such as the delegations representing governments in COP28. We hoped that these delegations would adopt human rights issues in the UAE, but they did not take up our cause in the manner we hoped for or expected. We, along with other human rights organizations, have made a great effort to communicate with states and governments, but their response was less than we expected.

The UAE government never responded to letters from UN special rapporteurs, nor to requests for UN visits to prisons or to the country in general, nor did they react to calls for reform. The irony here is that when the Universal Periodic Review (UPR) of the human rights situation in the UAE was released in May 2023, UN member states rightly expressed concerns about the level of human rights violations in the UAE. For example, the Dutch delegation to the United Nations Human Rights Council called for the release of Emirati detainees. But, the country’s delegation to COP28 did not issue any comment on the human rights situation during the climate summit. Other countries also adopted similar demands in the European Parliament, while not providing the same support during their participation at the COP28.

Did international attention affect the human rights policies of the Emirati government, whether by improving the conditions of detainees and their families or by facilitating the participation of journalists, activists, human rights defenders, representatives of civil society and indigenous groups at COP28?

The UAE did not provide any signs of improving the conditions of detainees. On the contrary, ahead of COP28, in June 2023, authorities transferred all the political detainees to secret prisons and held them there until December 1. During that period, we received mixed messages from within the UAE. While some said that the detainees were going through an intensive counseling period ahead of being released on National Day in the UAE on December 2, this enforced disappearance was most likely in order to conduct further interrogations without any oversight. These measures were taken right after the UAE received the UN’s universal periodic review recommendations about how to improve its human rights situation.

The UAE is a strong country, with enormous resources, and a government capable of exerting strategic international influence. Abu Dhabi has a huge network of influencers in policymaking in almost every country in the world. Therefore, it was not greatly affected by international human rights recommendations. Many believed that the UAE would send a positive message to the world by releasing detainees such as Ahmed Mansoor, Mohammed Al-Roken, and Nasser bin Ghaith, but the truth is that the UAE does not need to send positive messages to the world in light of the unconditional support that the government enjoys from its international partners.

As for journalists, environmental activists, and human rights defenders, the UAE authorities could not prevent their participation in COP28, but they completely controlled the activities that took place during the summit. Indeed, the UN institutions themselves refused to allow participants in COP28 to hold events demanding the release of Emirati prisoners of conscience. They forced participants to postpone these events and even controlled which banners were raised as well as the pictures of victims and slogans used. The human rights community believes that the UN acted in accordance with Emirati authorities’ conditions and instructions, which confirms the UAE’s influence within international institutions, including the United Nations.

The UAE Cybercrime Law (Federal Law No. 34 of 2021 on Combating Rumors and Cybercrimes) places many restrictions on the rights to peaceful assembly and association. How has this law affected the work of activists and civil society?

The Cybercrime Law, which was originally issued more than ten years ago, has imposed many restrictions on freedom of expression and severe penalties, such as imprisonment or exorbitant fines (some reaching one million UAE dirhams, or $270,000 USD), and both in most cases. And now, authorities have begun implementing the newest version of the law to curtail social media users’ freedom of expression.

This law has already affected Emiratis such as Nasser bin Ghaith, who was arrested after posting tweets criticizing the Egyptian government in the wake of the Raba’a Massacre. Bin Ghaith was accused of “publicly insulting” the country’s leaders, before he was arbitrarily sentenced to ten years. Similarly, Amina Al-Abdouli posted tweets about the Syrian revolution before she was arrested in 2015 and fined 500,000 UAE dirhams, or $136,000 USD.

While freedom of expression in the UAE had been very limited in scope even before the implementation of the law, there were still small virtual openings to exercise free expression. But after the issuance of this law, every margin of freedom of expression was eliminated.

This control extends beyond citizens to non-Emirati residents. For example, a foreign resident posted a video mocking the practices of some Emiratis. She was then arrested, convicted of insulting the UAE’s men and domestic workers, and sentenced to five years in jail before being deported. A similar thing happened to another resident of an Asian nationality who posted sarcastic video clips commenting on the spending rates of Emiratis. He was also imprisoned.

Notably, many victims of this controversial law were never released after serving their prison sentences. In the case of Amina Al-Abdouli, she was imprisoned in 2015 and spent almost a year forcibly disappeared in secret prisons, after which she was sentenced to five years in jail and transferred to Al-Wathba Prison. In the new prison, Al-Abdouli was able to communicate with the outside world and publish some recordings about the conditions in detention centers and prisons. She made calls to some other female prisoners and sent video clips to human rights and international institutions to document the violations she witnessed and faced. The UAE considered these messages an insult to the state’s reputation, and she was tried again and sentenced to an additional three years in prison. She completed this sentence on November 19, 2023, however, authorities have not released her yet.

Amina Al-Abdouli is not the only one. The authorities also arrested Maryam Al-Balushi and sentenced her to an additional three years on the same charges, and she was not released even after completing her sentence.

When talking about the violations faced by detained women in the UAE, we should not forget about what happened with Alia Abdel Nour, who died in prison due to medical negligence and the denial of essential cancer treatment.

Human rights organizations and the press have documented surveillance and espionage operations carried out by the Emirati government, including through the use of face and eye recognition tools and online communications monitoring. How did these practices affect the freedom and safety of COP28 participants and did they influence the events and discussions during the summit?

Authorities in the UAE have been censoring and spying on human rights defenders and government critics for a long time. In 2008, the Emirati government used spyware software to hack and spy on all BlackBerry phone users in the country. This was done with the help of telecommunications companies in the country. The Big Brother mentality of the Emirati government is apparent through its treating of citizens as subjects of surveillance. This is constantly confirmed through pro-government posts online, including those made on social media by influencers close to the UAE’s ruling elite, which send both implicit and explicit messages to citizens: “Be careful. . . . We are watching everything!”

The UAE also uses Falcon Eye cameras, which have been placed on every street in the country under the pretext of eliminating crime. But these cameras are highly advanced, technically complex, and use facial recognition and other techniques to obtain detailed data about people.

These UAE practices do not stop at the country’s borders. The government uses spyware and other censorship tools against officials, activists, and human rights defenders anywhere in the world. Personally, I change my phone constantly, because we remember what happened with the late activist Alaa Al-Siddiq whose phone was hacked using NSO’s Pegasus software while she was living in the U.K. This goes up to the highest levels: The ruler of Dubai, Mohammed bin Rashid Al Maktoum, used Pegasus to hack his ex-wife’s phone. Espionage has become a regular part of UAE governance and is used not only for political motives.

As for the freedom and safety of participants at COP28, there is a real threat in this regard. The UAE maintains a huge amount of data about actors and influencers everywhere in the world. Holding COP28 in the UAE allowed the country to expand this database to include all international influencers in the field of climate change. It can be said with confidence that the UAE government now maintains information on COP28 participants and those who wanted to participate in the summit, including their personal information, phone numbers, types of computers and phones they use, and their passport information.

In the absence of a legal framework to protect the privacy of participants at such events, the UAE exploits this information for many purposes, starting with connecting with participants and influencers to promote the official state narrative about the UAE. I firmly believe that the UN and its institutions made a grave mistake when they shared participants’ data and information with the UAE government in the absence of any guarantees to protect the privacy of participants and without any mechanism in place to hold Emirati authorities accountable should this data be leaked or used for purposes other than which it was originally intended.

I personally experienced a similar situation. X (formerly Twitter) users close to the Emirati government used my personal data and photo in the government’s passport system to defame and attack me.

In the wake of the war on Gaza, there has been what many call “international indifference” toward increasing human rights violations in the region, which contributes to creating an environment conducive to the growth of tyranny. How is this reflected in the UAE case? Can the international community help support the aspirations of the Emiratis and the people of the region for freedom and democracy?

The disregard for Israeli violations sends a message that there are issues more important than human lives and human rights, and that the lives of children may be cheaper than demanding a ceasefire. This was clearly evident in the bias against victims and the indifference to the huge number of Palestinian civilian victims displayed by the media and governments in the West. This disregard is reflected in policies toward countries with records of human rights abuses.

The international response to Israel’s atrocities in Gaza is shortsighted and ignores the violent repercussions of injustice and systematic oppression. I have seen Emirati citizens join violent extremist groups and declare dissidents and human rights activists as “infidels” even before they criticize the government. The main reason for this is their level of despair, having lost hope in seeking justice through legitimate means and in the ability of international institutions and laws to deliver justice. Therefore, it is sad and dangerous to see world governments such as Germany, France, and the United States support the Israeli massacre of civilians in Gaza while ignoring human rights, which are guaranteed by international law. Even more dangerous is that certain groups have gained legitimacy due to their position rejecting the Israeli war, as shown through growing support for the Houthis from a large number of Arabs and Muslims, despite the widespread human rights violations they have committed in Yemen over the years.

On the other hand, the Abraham Accords, and the UAE’s rapprochement with Israel, provided the UAE with immunity against accountability for its human rights violations. Israel has become one of the most active defenders of the UAE and one of the promoters of the Emirati government’s propaganda around the world. It goes both ways. For example, the European Parliament canceled a hearing in which I was participating prior to COP28, due to Emirati, and perhaps Israeli, complaints about some posts I had made previously rejecting Israeli violations in the Palestinian territories.

The UAE, like many countries in the region, wants the benefits of being an active member of the international community without the responsibilities. Despite hosting one of the most important United Nations summits, it ignores concerns raised by UN experts on the human rights situation in the UAE since 2013. How can the human rights community highlight this contradiction and push the UAE to abide by international laws and agreements?

One of the main problems in dealing with the UAE is the general lack of knowledge about the negative role that the UAE plays on the international stage. Therefore, we must take advantage of the awareness raised during COP28 about the UAE’s ongoing human rights violations. This must turn into specific demands, such as insisting that the UAE can not be allowed to host similar conferences before amending its legal system to ensure the privacy and safety of citizens and participants, abolish restrictions on peaceful assembly and freedom of opinion and expression, and most importantly, release all prisoners of conscience.

The Expert

Hamad Al-Shamsi is an Emirati human rights activist and the executive director of the Emirates Detainees Advocacy Center (EDAC). He has lived in self-imposed exile outside the UAE since 2012. While outside the country, he was added to the UAE94 case and was sentenced in absentia to 15 years in prison. In response to Al-Shamsi and other Emirati activists founding EDAC in 2021, UAE authorities added him to their terrorism. The authorities added him to another case in which he was sentenced to an additional fifteen years before recently adding him to the UAE84 case, in which the sentence is expected to be either life imprisonment or even death. Find him on X @Alshamsi789.

The Authors

Abdelrahman Ayyash is a senior program manager at MEDC. He is a seasoned journalist, researcher, and translator with a focus on Islamic movements, civil-military relations, and human rights. Holding an M.A. in Global Affairs, Ayyash specializes in the Middle East and North Africa. He is co-author of the book “Broken Bonds: The Existential Crisis of Egypt’s Muslim Brotherhood, 2013–22” (2023), and has translated three books on civil-military relations and the Muslim Brotherhood. Find him on X at @3yyash.

Yasmin Omar is the director of the “Democracy Matters” Initiative at MEDC. She is an international human rights lawyer with a dedicated career focused on defending victims of human rights violations. Omar earned an LLM in international law from Syracuse University College of Law and holds a bachelor’s degree in law from Cairo University. Find her on X at @yasminoviech.

Acknowledgment

The authors wish to thank the Heinrich Boell Foundation, Washington, D.C., for its support of this publication.